The third in a series of three about the use of race in affirmative action.

Having found that classroom diversity is a compelling government interest, the court battle going forward seems to center on the “narrowly tailored means” used to implement a diversity objective. To achieve diversity that is not centered in race requires an admission processes that looks at a diverse set of signifiers. If race is used as a factor, it must be done so only after making a good faith effort to achieve diversity with race-neutral methods.[1] The Fisher Court requires “a careful judicial inquiry into whether a university could achieve sufficient diversity without using racial classifications.”[2]

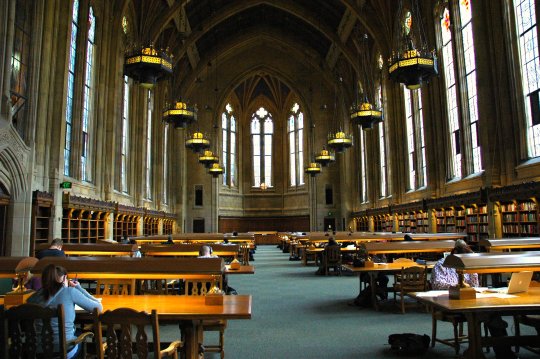

Photo by Wonderlane on Flickr CC BY 2.0.

As Justice Ginsburg has pointed out, general diversity may in fact be racial diversity in “camouflage.”[3] By constructing an admissions system that looks at socioeconomic background, employment history, family composition, age, religion, gender, and any number of characteristics, a school may still seek racial diversity by simply calling it something different. Be it viewpoint, life experience, or something more holistic, the general diversity insisted on by the Court could be sidestepped.[4] For example the University of Texas generally reports enrollment statistics in essentially only race and ethnicity categories.[5] This is nothing unique, at least in terms of demographic reporting.[6] University public relation campaigns in general can often be seen as focusing more on the ethnic diversity of its admitted students than the incoming class’s scholastic qualities and achievements. While race statistics are undeniably valuable in identifying and treating disparities, it is easy to see why discrimination suits arise under diversity-minded admission policies when schools are seemingly most interesting in showing off the degree of student and minority diversity that they have fostered.

Despite the accepted benefit of a diverse learning environment, the use of race-neutral characteristics in admissions creates the risk of enforcing minority stereotypes. If a school is interested in having a racially diverse student body, be it consciously or not, such a program would likely pass legal scrutiny under Fisher if the school employs race-neutral language and methods to achieve it. The danger of using race-neutral identifiers to produce racial diversity is that the school could end up admitting students because they meet the stereotypical qualities of a given minority. There may be the tendency among schools to look at the stereotypical spoken language, family composition, birthplace, or even religious belief of a targeted minority, and then create an admissions policy based on those characteristics. This could in turn lead to admitting students who strongly resemble a desired minority profile even though such profiling is inconsistent with the overarching ideals of diversity. Achieving racial diversity through race-neutral factors could in essence create a synthesized classroom of stereotypes. Such results directly conflicts with the Court recognized goal of diminishing stereotyped understandings.[7] To truly break free of racial stereotyping in the classroom, we must start by removing it from the admissions process itself.

Conclusion

The Court’s recognition of classroom diversity as a compelling government interest when viewed with the realities in which schools operate justifies the use of race as a factor in the college admissions process. It seems problematic to allow schools to pursue diversity and not be able to address race head on. Though race in a vacuum by no means defines who someone is or how she thinks, we live in a society where race is constantly analyzed, for better or for worse. The Fourteenth Amendment’s protection against the unequal application of the law due to race both accepts this reality while rejecting the injustice it can create. Unless the court overturns classroom diversity as a compelling government interest, or we as a country truly move to a point where race is not generally viewed or tracked as an identifier, race needs to remain a tool in creating a realistic and beneficially diverse learning environment.

[1] See Fisher, 133 S. Ct.

[2] Id. at 2411.

[3] Gratz, 539 U.S. at 304 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

[4] See Bakke, 438 U.S. at 407 (Blackmun, J., concurring in part) (“I presume that that factor always has been there, though perhaps not conceded or even admitted”).

[5] _See _The University of Texas at Austin, 2012-2013 Statistical Handbook Quick Reference Guide (2012-13), available at http://www.utexas.edu/academic/ima/sites/default/files/IMA_Pub_QuickReference_2012_Fall.pdf.

[6] See e.g. The University of Utah, Headcount Enrollment by Academic Level, Gender, and Ethnicity (2008)_ available at _http://www.obia.utah.edu/ia/stat/2008-2009/ss0809A02.pdf.

[7] See Fisher, 133 S. Ct. at 2418.